„…daß wir Kindern zwei Dinge geben sollten: Wurzel und Flügel. Wurzeln, die Halt geben, man weiß, wo man hingehört, aber eben auch Flügel, die einen helfen, sich aus seinen Zwängen und Vorurteilen zu lösen und einem auch ermöglichen auch andere Wege zu gehen (oder besser zu fliegen).”

'…There are two things children should get from their parents: roots and wings. Roots to give them bearing and a sense of belonging, and wings that relieve the one from constraints and prejudices and give the other the opportunity to travel (or rather, fly) new ways.'

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

In Béla Bartók's age a wide gap separated the middle classes and thier culture from the peasantry. The peasantry's organic culture features an ability to absorb various external influences and render them in its own image. Urban life had a penchant for imported patterns, and it seemd that Hungarian civil society would lose its autochthonous character. A need for renewal emerged in high art, and in consequence, many were taken to exotic lands or the „unquestionably heroic” historical past. Bartók, however ventured over to the other side, that nearby terra incognita whose exploration would change his life. He discovered the roots of Hungarian musical culture that gave him the power to ascend to hitherto unimaginable heights.

What would Bartók have seen and heard in early 20th-century Hungary's villages? What did the magic of the milieu consist in – a magic whose inner essence Bartók sought to express? The shepherd pipe, the peasant women's woven, sewed and embroidered dress, the young farmer's virtuoso dance, or even the beggars' hurdy-gurdy performance were all imprints of a culture whose be-all and end-all was an expression of a Magyar identity. In Bartók's Central Europe, owing to the individually „tailorable” character of folklore, anybody could become „somebody”. This world – with its candid manifestations totally lacking affectedness – revealed to him the hidden dimension of an art that never made it into the lexicons of art history. While most such books still fail to regard folk art as an art, Bartók's oeuvre significantly contributed to traditional musical culture's gaining international recognition and acceptance in the bourgeois parlours of his age.

Folk music, like many other manifestations of folklore, is a gripping expression of a system of values and patterns of behaviour that collectively comprise the character of a national culture. Musical tradition is a part of a complex cultural heritage, whose tragically swift disintegration turned Central European societies upside down by the end of the millennium. Bartók had become aware of the prespect of this cultural loss, and with the benefit of hindsight it can be established that he chose one of the most effective languages – the means of high art – to issue a warning signal. His exceptional talent and the originality of his art led to a break from Romanticism, marking the beginning of a new era in European art music.

This recording features Bartók's violin duos together with the folk-origin melodies (and the related versions of each song type) that directly inspires those works. Also, it presents the folk music of regions where the composer conducted mucal-folkloristic fieldwork; and melodies from our own collections have also been added to the parallels. When selecting the folk music for this record, we did not adhere strictly to the composer's own recordings or song varieties, and often the idea was simply to conjure up an atmosphere. We made every effort, however, to authentically render the folk melodies, as Bartók himself would have heard them. In his life-time a concert-hall performance of authentic folk music would have been unthinkable. However, that has changed, and in the 1970s an avant-garde musical trend emerged in Hungary that made the authentical performance of peasant music its chief means of expression. We believe that the values of traditional musical culture can and should be mediated in „unpolished form”, for they possess a musical language that is universally understood in that original, genuine form. Which is why the crystallised peasant performance and the art music inspired by it work well side by side. Bartók himself never sought to make folk music more palatable to his audiences by means of folk-inspired works. „[…] in ancient Magyar peasant music we discovered the foundation that could finally serve as a basis upon which high Hungarian art music could be established”, he wrote.

This recording presents the melodic parallels between authentic folk music and Bartók's works, as well as the instrumental virtuosity characteristic of in both musical worlds. Typical examples include not only the violin but also the piano parts in Rhapsodies Nos. 1 and 2 . These works are counted among the most difficult-to-play pieces in the composer's oeuvre. The performance of the many diverse forms of instrumental and vocal folk music of the Carpathian Basin also require a great amount of study and technical skills. The Transylvanian dance music (2, 3, 4) on this record, together with their Slovak parallels (4), the new-style Magyar tunes (14), the works for bagpipe and their imitations for violin are representative of different instrumental practices and musical styles. The ahead-of-its-time concept by which Bartók considered it important to reveal and preserve the musical traditions of Hungary's neighbouring countries and the complex approach of attributing equal importance to the values of Magyar, Romanian, Slovakian, Ruthenian or Southern Slav traditions is central to our own musical profile, too. The multi-languange folk songs on this record were not selected specifically for this occasion, but rather, reflect our long-term efforts to perform the folk music of the neighbouring countries.

In the performance of Bartók's works the idea was to reveal the musical-cultural parallels and interactions the composer himself frequently stressed , and the concept, according to which „[…] the important thing is to introduce to our music the indescribable inner character of peasant music; moreover, the'air', so to speak, of the whole of peasant music-making.” This interaction is presented by leading Hungarian classical musicians, as well as folk musicians who, following in Bartók's footsteps, are involved in folk-music collection and publication, and who seek to translate their researches into performance practice. „The fact that we need to conduct collections ourselves instead of learning the melodies from ready written or printed collections, has become a truly momentous issue”, Bartók wrote. And this learning precess is perhaps even more significant for the stage performers of folk music. We believe that the experience gained the during fieldwork among the repositories of authentic folk music has translated into tangible values in our recordings and concerts.

Gergely Agócs

English Translation by Miklós Bodóczky

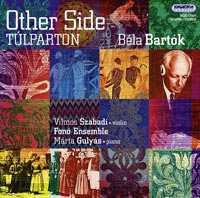

Other side

BARTÓK

Art Music and its Folk Roots

1. The sun rises not where it used to rise ( Ihod, Romania ) 1'11”

2. I am but a fatherless orphan ( Hodoşa, Romania ) 1'48”

3. Green lament ( Petrilaca de Mureş, Romania ) 4'07”

4. Mongrel, Turner ( Petrilaca de Mureş, Romania ), Krucena ( Raslavice, Slovakia ) 13'07”

5. Hey, good night ( Čierny Balog, Slovakia ) 1'21”

6. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 1 – Teasing song 0'58”

7. I light my fire, Two penoies ( Transdanubia, Hungary ) 3'43”

8. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 37 – Prelude and canon 2'36”

9. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 36 – Bagpipes 1'01”

10. The barrel is little ( Žirany, Slovakia ), Čie sa to kone ( Salakusy, Slovakia ) 2'27”

11. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 8 – Slovak song 1'07”

12. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 9 – Play 0'38”

13. In the fishpond at Péterfala ( Petrovce, Slovakia ) 1'30”

14. I sat on the hearth – Mári Bozse's goose ( Highland, Hungary ) 1'53”

15. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 15 – Soldier's song 0'50”

16. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 17 – Marching song (1) 0'44”

17. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 18 – Marching song (2) 0'42”

18. Uccu, dárom, danárom – I caught a mosquito ( Transdanubia, Hungary ) 2'33”

19. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 20 – Song 1'18”

20. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 22 – Mosquito-dance 0'39”

21. Ruthenian wanderer's song and kolomeika ( Tjachiv, Ukraine ) 1'56”

22. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 23 – Wedding song 1'18”

23. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 35 – Ruthenian kolomejka 1'04”

24. Kétegyháza and Elek lunga 2'06”

25. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 38 – Rumanian whirling dance 0'46”

26. B. Bartók: Duo for Two Violins No. 44 – Transylvanian dance 1'55”

B. Bartók: Rhapsody No. 1 9'07”

27. I. Slow 3'50”

28. II. Fast 5'16”

B. Bartók: Rhapsody No. 2 11'45”

29. I. Slow 4'15”

30. II. Fast 7'29”

31 I am a bride, too ( Highland, Hungary ) 1'56”

Total time: 76'13”

Fonó Orchestra

Ágnes Herczku – song: 1, 2, 4, 7, 13, 24, 31

Gergely Agócs – song: 4, 5, 10, flute: 2, bagpipe: 7, cross-flute: 18, long shepherd's pipe: 18

Tamás Gombai – violin: 3, 4, 6, 8, 9-12, 15-17, 19, 20, 22-26, violin accompaniment: 14

István Pál „Szalonna” – violin: 3, 4, 14, 21, violin accompaniment: 24

Sándor D. Tóth – viola: 3, 4

Zsolt Kürtösi – double bass: 3, 4, 14

Vilmos Szabadi – violin: 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15-17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 25-30

Márta Gulyás – piano: 27-30

Contributors: